Orange Mound A Black Community in Memphis honored by former 1st Lady Michelle Obama in 2016 as a “Preserve American Community” honors “White Supremacy & Slavery” via its association & embrace of Deaderick Plantation, not inclusive of the community

MEMPHIS, TN, June 19, 2025 /24-7PressRelease/ — Memphis, Tennessee, the most populated city of Black people in America, strikingly features a cotton museum but lacks a dedicated “Black Memphis History Museum.” This glaring omission underscores a deeper, pervasive struggle that Anthony “Amp” Elmore, a Memphis-born 5-time World Kickboxing champion and revered Black Memphis historian, is fiercely confronting: entrenched White Supremacy, systemic Racism, and destructive Black on Black Racism.

This news story is a part of “Juneteenth.” Juneteenth, officially known as Juneteenth National Independence Day, commemorates June 19, 1865, when Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation—freeing the last enslaved Black Americans in the Confederacy. It became a federal holiday in 2021, making it the youngest federal holiday in the United States. Also in 1865 was the end of the John Deaderick Slave Plantation in Memphis, Tennessee, whereas in Memphis, Tennessee the John Deaderick Slave Plantation is racially associated to the Black Orange Mound Community in Memphis, Tennessee.

Memphis, Tennessee unknown and untold was once “The Slave capital of the world” whereas the history of “Orange Mound in Memphis” is related to slavery in America and an extension of “Jim Crow laws and culture in America. Click here to see and hear video titled; “Barron Deaderick used White Supremacy to Falsely Connect Orange Mound to Plantation–Truth Revealed.”

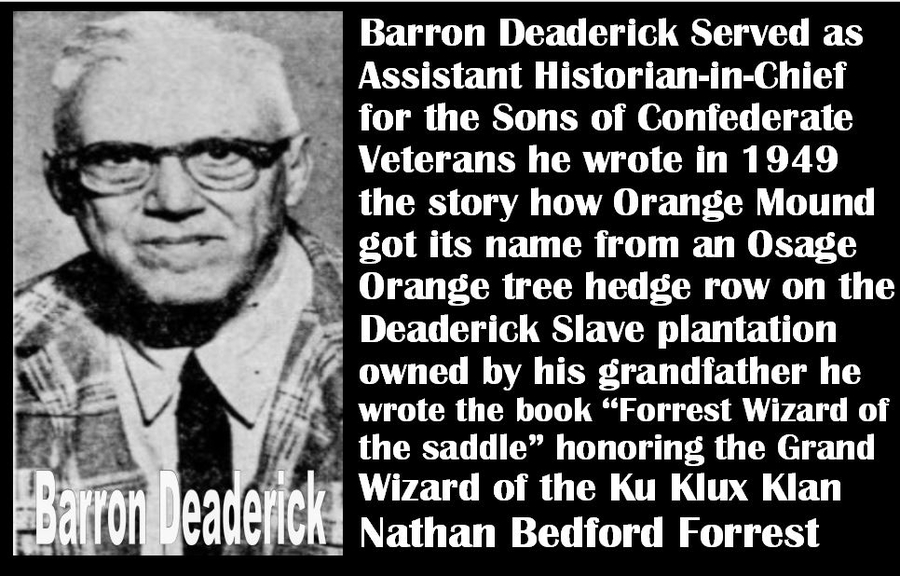

John Barron Deaderick an honored historian for the “Sons of Confederate Veterans” whose work “Wizard of the Saddle” immortalized the story of Nathan Bedford Forrest the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, whose Grandfather enslaved Africans to his plantation in Memphis, Barron Deaderick’s greatest Memphis influence was his 1849 work titled “How Orange Mound Got its name.” The city of Memphis adopted the history of Orange Mound “Strait out of the Sons of Confederate Veterans Play book.”

In today’s language Barron Deaderick would be called an “influencer” whereas this White Historian who represents the “Sons of Confederate Veterans”was able to exert his greatest influence regarding the history of “The Black Orange Mound Community in Memphis.”

In 1871 the Deaderick Family created “Melrose Station” about 150 acres in what is known today as “Orange Mound.” The intent of the Deaderick’s was to create an affluent suburban community for White people. The yellow fever epidemic of 1878 shattered any hopes of such an affluent White community.

In 1878 it was reported that fear of the Yellow fever caused 25,000 Whites to leave Memphis in 3 days. Unknown and untold as a part of “Black Memphis History” Blacks saved Memphis, whereas it was Black people who was not severely killed by Yellow fever had to take care of the sick, dying bury the dead and clean the city whereas the Black militias were the police.

In 1879 Memphis lost its charter and became a taxing district. There were 14,000 Blacks and 6000 Whites left in Memphis. Fast forward to the October 18, 1949 the story by Barron Deaderick titled: “How Orange Mound Got its name.” The first paragraph reads: “The Negro subdivision in the Eastern section of Memphis, known a “Orange Mound , got its name from a large Osage Orange hedge row which extended from North to South on the Eastern side of the original plantation.”

The critical and untold story omitted by Barron Deaderick is the 1871 documented story of “Melrose Station.” What is called “Orange Mound Today” was “Melrose Station” in 1871, instead the Yellow Fever drenched all hopes of there being an affluent White suburb instead emerged a historic Black Community called today “Orange Mound.”

In the story “How Orange Mound got its name” Barron Deaderick in the last paragraph wrote: “The present Spottswood, Park, Deaderick, Barron, Hamilton, David, and Speed avenues and street run through what was formerly the John George Deaderick plantation, and were named by my grand-father , “Mike Deaderick.”

What is unknown and untold in Memphis is the story of “Melrose Station” whereas Michael and William Deaderick platted a community for Whites called “Melrose Station” that is “Orange Mound” Today. What is untold is how the Yellow fever epidemic of 1878 changed the fate of Blacks whereas Blacks created their own community outside of White masters.

On August 28, 2013 Black Anthropologist Dr. Charles Williams who Director of Graduate studies Department of Anthropology University of Memphis published the book “African American Life and Culture in Orange Mound: Case Study of a Black Community in Memphis, 1890-1980” clearly knew about Barron Deaderick as he mentioned in the book, Dr. Williams immortalized the slave holder’s family narrative about the Deaderick Family.

On the cover of the book Dr. Williams picture the “Orange Mound Historical Marker” that notes Orange Mound got its name from a row of Mock Orange Shrubs on the side of the yard of the Deaderick home. The evidence presented that the name of “Orange Mound “ came from a row of Mock Orange Trees on the Deaderick plantation is questionable and a rewrite of Black History written by Barron Deaderick as noted by Elmore.

On February 4, 2013 A PBS documentary premiered on WKNO television in Memphis titled: A community called Orange Mound. White film director Jay Killingsworth and his wife Amy Killingworth produced an amazing documentary of the Orange Mound community however the documentary omitted the influence of “Sons of Confederate Historian Barron Deaderick” whose connection falsely connects Orange Mound to the Deaderick Plantation. Click here to see the amazing 2013 documentary Jay Killingsworth film titled: A Community called Orange Mound.

On May 20th, 2025, Elmore took a monumental step, filing a Federal Lawsuit against numerous city and county entities, including the City of Memphis, Shelby County, Memphis Tourism, the Shelby County Historical Commission, and various arts and film organizations. Elmore ask the Tennessee Historical Commission to show evidence that the name Orange Mound came from a row of Mock Orange Trees on the Deaderick Plantation.

Elmore’s aim is to ignite international attention on Memphis’s deeply rooted racial injustices, particularly as they impact “Orange Mound,” the first community in America built for and by African Americans. Elmore’s lawsuit is a clarion call for truth, justice, and the overdue establishment of a “Black Memphis History Museum.”

Memphis’s history is stained by its racial past. In 1978, amidst the tumultuous police and fire strike, the Wall Street Journal famously condemned Memphis as “A Backwards City with a plantation Mentality.” While symbolic victories have been won—like the removal of the statue of Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest in 2017 and Ku Klux Klan leader Clifford David’s image from a Federal building in 2022—the underlying systemic issues persist. Elmore notes “The name Orange Mound should not be connected to the Deaderick Plantation.”

Anthony “Amp” Elmore’s fight is not just in a court room or asking the United Nations for help. Elmore is a filmmaker and artist. Click here to see and hear the January 27, 2025 Elmore release of an educational Music video on You Tube titled: Black Man Refuse to be A Slave From Orange Mound Video

At the heart of Elmore’s legal and historical battle is the contested origin of the Orange Mound name. He vehemently challenges the widely circulated, yet unsubstantiated, narrative that the community’s name derives from “Osage Orange trees” on the former Deaderick Plantation. Most important Elmore notes that “Orange Mound should not be associated to the Deaderick Plantation in any way. Elmore notes that the birth of Orange Mound should be listed in 1879 with the birth of two Black Churches that exist in Orange Mound today. Mt Moriah and MT Pisgah Baptist Churches.

Elmore asserts that the to connect Orange Mound to the John Deaderick Plantation is a deliberate historical fabrication, meticulously crafted and perpetuated by Barron Deaderick, an alleged White Supremacist Historian for “The Sons of Confederate Veterans,” who wrote the book “The Wizard of the Saddle” honoring Klan Leader Nathan Bedford Forrest, a voice that endears Black Orange Mound to his once Family’s Deaderick Plantation.

“This narrative is a racist act,” states Elmore, “designed to connect Black achievement to White Supremacy. Elmore’s extensive research confirms there is absolutely no evidence supporting the ‘Osage Orange tree’ origin prior to Barron Deaderick’s October 18, 1949, article titled: ‘How Orange Mound Got its Name.’ In 1949, during the rigid segregation of Jim Crow, there was hardly such a thing as ‘Black History’ acknowledged in America. This allowed Deaderick, a Confederate historian, to appropriate Orange Mound’s history unchallenged, and his myth has since been assumed as truth by all historical accounts.”

Elmore presents compelling historical facts that dismantle the fabricated link to the Deaderick Plantation: The Civil War definitively ended in 1865, meaning the “Deaderick Plantation” ceased to exist as a functioning slave-holding entity. Elmore question is simple how could the name “Orange Mound” being associated to the Deaderick only come up 60 years in 1949 when Barron Deaderick alleged the name comes from a row of Orange Mound Hedge Grove plants on the Deaderick plantation.

Barron Deaderick was born in 1886 21 years after the Civil war ended. In 1883 Black MT Moriah Baptist Church purchased the land where the Church sites today before Barron Deaderick was born. In Dr. Williams book on Orange Mound noted that those who lived early in Orange Mound noted the land at the time of Barron Deaderick’s birth was a Cotton Field whereas he never saw the Deaderick home house.

The 1890 U.S. Census reveals Shelby County’s population was 112,713, with 61,613 (or 55%) being African American. This significant demographic presence confirms a robust Black community that would undoubtedly have had its own established names for its community. Elmore asserts that E.E. Meacham got the name “Orange Mound” from the residence living in the community prior to purchasing the land to sell.

Prior to E.E. Meacham’s land purchase in 1890, Mt. Moriah Baptist Church, an African American institution, acquired its land in the area in 1883. This demonstrates a strong, pre-existing Black community with evident self-organization.

Further evidence of Black agency in naming is seen in the 1910 Bank of Commerce and Trust advertisement for “Montgomery Park Place”—a “High-Class Restricted Subdivision for Colored People” within what became Orange Mound, featuring “large homes with big lots.” This highlights the deliberate marketing to and self-identification of Black residents, entirely separate from any plantation association. The historical precedent of “Mound Bayou, Mississippi,” founded by African Americans in 1887 and incorporating “Mound” (a term associated with Native American earthworks) in its name, provides a powerful parallel for Black self-naming practices.

The vast tract of land once held by the Deaderick family was fragmented after the Civil War into various distinct Memphis landmarks, including the, Pink Palace Memphis, Christian Brothers College, Charleston Railroad, Liberty Pocket Park (now the fairgrounds), Memphis Country Club, Chickasaw Gardens, Liberty Bowl Stadium, and the area known as “Beltline.” “What is clear,” Elmore emphasizes, they don’t refer to these locations as the former Deaderick Plantation.

‘Orange Mound’ has no inherent association to the Deaderick Plantation. Without Orange Mound, the Deaderick Plantation has no significance. Its only place of glory is that Barron Deaderick was able to use his influence to subject “Orange Mound” to be part of “The Deaderick Plantation.” Barron Deaderick in 1949 used “White Supremacy” via appropriating “Orange Mound” an independent Black Community named by Blacks themselves, like in days of Slavery a White could simply take credit for Black achievement.

This is the question Elmore asks: did the Deaderick plantation create Orange Mound, or did Orange Mound create the Deaderick Plantation?

Elmore asserts that Barron Deaderick’s 1949 narrative was a calculated act to impose a white supremacist lens on Black achievement. This deliberate misdirection has been perpetuated by a culture where, as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stated, “Silence is Betrayal”—a silence Elmore attributes to a troubling “Black on Black racism” among certain elected African American leaders in Memphis who fail to challenge the Barron Deaderick’s appropriated history. Elmore notes; many Black leaders in Memphis do not have the courage to question the Barron Deaderick narrative.

Elmore notes that no plantation would decorate its property with an Osage Orange tree, whereas the trees were used for fencing before barbed wire was invented. Most importantly Elmore notes that Whites did not use the world “Mound.” Mound is always associated with Native Americans.

Elmore’s lawsuit details a broader pattern of systemic discrimination and historical erasure in Memphis:

Suppression of Black Cinematic History: Elmore’s 1988 film, “The Contemporary Gladiator,” holds the unprecedented distinction as the first kickboxing film in world film history and Memphis’s first independent 35mm theatrical film, produced primarily within the historic African American community. Despite its international premiere in Nairobi, Kenya (1990), and its acquisition by Germany in 1989 (retitled “Kickbox Gladiator” can be used for German language education), the film’s significance has been “intentionally ignored, dismissed, and actively suppressed” by various Memphis entities.

Elmore notes that the Memphis Shelby County Film Commission, under Linn Sitler (her first client), even installed a historical marker in 2007 honoring white filmmaker Jim Jarmusch as Memphis’s first independent 35mm filmmaker, despite her prior knowledge of Elmore’s earlier work. “The Contemporary Gladiator.“

He further claims that The Commercial Appeal, with writer John Beifuss and Linn Sitler, has actively suppressed any story about Elmore and his films. The saving grace for Anthony “Amp” Elmore is not only Turner Classic movies, T.V. Guide, IMDB, Click here to read November 22, 1987 L.A. News Story titled Films going into production “The Contemporary Gladiator.

Neglect of Black Cultural Initiatives: The lawsuit highlights the “systemic lack of support for Black cultural and historical initiatives,” contrasting this with significant investments in other areas like Liberty Park. Elmore alleges “Black on Black Racism” from Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris, who is accused of prioritizing other initiatives and granting a “Forever Lease” to the Orange Mound Arts Council, which Elmore claims is a “fraudulent entity lacking community engagement and transparency.” He also cites Toni Holmon Turner, Public Affairs Manager of Parks, City of Memphis, for denying him permission to film at the Orange Mound Senior Citizen Center, characterizing it as “Black on Black Discrimination.”

Click here to read the Anthony “Amp” Elmore lawsuit against the City of Memphis.

Erasure of African Connections: Former Black Memphis Mayor Dr. W.W. Herenton is cited for rejecting family, education, and cultural trade initiatives with Africa, and Mayor Lee Harris is accused of disrespecting African dignitaries during the Memphis Bicentennial. Elmore’s film “200 Years of Black Memphis History” was excluded from the Memphis Bicentennial Celebration, and his “African Cultural Diplomacy” initiatives, including the “Barack Obama Heritage Tour,” have allegedly been suppressed.

Unequitable Tourism Benefits: Elmore states that Memphis Tourism, under Kevin Kane, engages in “bias and racism,” leading to a lack of equitable economic benefits for Black individuals and businesses despite Memphis’s rich Black history. He starkly asserts that the city is “pimping” the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., with white-owned entities disproportionately benefiting from tourism related to his assassination, while Black-owned businesses are marginalized. He also emphasizes that the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was created in part due to the horrific Memphis Massacre of 1866, a pivotal event often inadequately acknowledged in tourism narratives.

Anthony “Amp” Elmore is demanding comprehensive relief, including: the creation and funding of a Black Memphis History Museum in Orange Mound; formal and public acknowledgment of “The Contemporary Gladiator” as a landmark of World Black History, including its submission to the United States Congressional Film Registry; an investigation into the Orange Mound Arts Council; injunctive relief against discriminatory tourism practices; and correction of the historical record by the Shelby County Historical Commission, The Commercial Appeal, and other entities.

With this landmark Federal Lawsuit, Elmore is not only seeking justice within the American legal system but is also actively pursuing assistance from the United Nations. He aims to bring international pressure to bear on what he identifies as a deeply ingrained system of historical erasure and racial injustice in Memphis, ensuring that the true, self-determined history of Orange Mound and Black Memphis is finally recognized and celebrated.

The section of South Hollywood Street between Union and Southern Avenues in Memphis has been renamed in honor of Glenn Rogers Sr., the first Black football player at Memphis State. It is now officially called Glenn Rogers Sr. Street. This renaming ceremony took place on October 25, 2024.

Anthony Elmore notes that naming a section of South Hollywood is an easy call. Elmore ask what would be called a radical idea for Memphis historic African/American community of Orange Mound that has a 99% African/American population whereas “Orange Mound is the 1st planned Community in America built for Blacks by Blacks.

On January 13, 2022 Anthony “Amp” Elmore released an almost 3 hour video titled: Orange Mound A Black Lecture Critical Race Theory Black History Month Movie. Elmore rented the Malco Studio on the Square to premier the movie. Click here to see the movie on you tube to learn the more detailed Black untold story about Orange Mound.

Elmore ask Black Memphis elected officials to rid the community of Orange Mound of the “Slave Master Deaderick Name.” Historic Melrose School in Memphis is located at 2870 Deaderick Avenue in “Orange Mound.”

Elmore notes while the “Sons of Confederates Veterans” and many Whites would be upset that some Black Memphis leaders would have the courage to empower not only their community it would empower Black America if Black Memphis elected officials would remove and eradicate the slave master Deaderick name out of “Orange Mound” and empower the community with a name like “Black Gold Medal Avenue” to honor the 3 Melrose high school Gold Medal winners “Rochelle Stevens, Kennedy McKinney and Shelia Echols” renaming”Deaderick Avenue” to Gold Medal Avenue.

Most important Elmore encourage Orange Mound to rid itself of the false Barron Deaderick Osage Orange Tree narrative.

The Orange Mound News Network (OMNN). Founded by Anthony Amp Elmore, OMNN aims to reclaim and reshape the narrative of Orange Mound through the power of filmmaking, education, and content creation. Our goal is to challenge the negative stereotypes and biased portrayals that have long plagued our community, creating a positive space for family, Black culture, history, and education.

—

For the original version of this press release, please visit 24-7PressRelease.com here